The Country That Doesn't Really Exist

A few days spent in weird, weird Abkhazia

The bridge is empty except for a mule-drawn carriage bumping slowly northward. It’s been so long since this was used as a road, yet a few pieces of tarmac still cling stubbornly to the surface. Most of the old highway has been worn down to dirt, and much of that dirt has been worn down to potholes from the dozens of winters since a car last passed this way. The bridge is low, spanning a broad, dry riverbed that’s just dusty grass and splotchy wildflowers blowing in the noon breeze. The mule cart gets stuck momentarily in a deep pothole, and the suitcase strapped to the back falls lazily into the dirt road, its dull thud failing to produce an echo.

I jump down from the carriage to grab the suitcase and tuck it back into the strap behind the seat, disregarding the futility of the act. This is ridiculous. We’ve been jostling across this bridge for 15 minutes already, and have lost this case about 10 times. Behind us, another traveller has arrived on the bridge. He’s carrying a big wheely suitcase with one arm, but closes the ground quickly. We trundle on. Soon, he’s upon us, smiling and waving. He says something friendly as he easily overtakes us, but I don’t understand the words. I don’t even know what language he’s speaking. Here, it could be one of a few.

My bag falls off a few more times but before an hour has passed, we’ve managed the 800 meters and reached the other side of the bridge. The driver grins a big toothless grin and gestures toward a bend in the road ahead. “There,” he probably says. It’s very slushy, and again might not be in English. It’s hard to say. He laughs and slaps my back. It’s the last human warmth I’ll experience for a few days, the end of Georgian hospitality and the beginning of something far, far stranger.

I grab my suitcase and duffel bag and attempt that weird wave where you have both hands full and just kind of flap your arms low by your sides, then turn and walk toward the bend in the road. Walking is so much faster than the mule cart, even with the bags, but I’m uneasy. There’s a kind of heaviness in the air, like a storm forming. Soon, I’m at the bend in the road, and my uneasiness finds its source. Before me lies a tall barbed-wire fence, many chunky green military vehicles, some German shepherds, and people in headscarves and heavy coats waiting in a long line at a truly bizarre frontier.

Here lies the border of Abkhazia, one of the world’s unrecognized nations.

Abkhazia has an old history, but most of it is really boring. I’ll attempt a quick recap.

It was a vassal state under the Byzantines and later became part of Georgia and then part of the Ottoman empire. Ugh. See what I mean?

Byzantine, Georgian, Ottoman. That covers almost 2,000 years of history until things get interesting as the Soviet Union starts to crumble. Georgia declared its independence in early 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, and by 1992 Abkhazia is at war with Georgia. A staggering 30,000 people are killed in this conflict, which lasts almost two years. Many Georgians are expelled, leaving Abkhazia with a population of around 250,000. In 1994 a ceasefire begins, with Russian troops forming the majority of the peacekeeping force. You can probably see where this is going.

Russian troops never leave Abkhazia, and in 1999, Abkhazia declares its independence from Georgia. Georgia ignores this. In fact, most countries in the world have ignored this, with only Russia (who didn’t even recognize Abkhazia as an independent nation until it was strategically beneficial to do so in 2008, as South Ossetia was also forcefully trying to leave Georgia) recognizing its independence. Most of the jurisdictions that recognize Abkhazia are themselves newly formed micronations of dubious provenance, and Venezuela and Nicaragua.

This is not really going to be a treatise on statehood and identity. This context is the bare minimum required to really get down to business at hand: trying to explain the deep weirdness and peculiarities of this little country that doesn’t quite exist.

Before the rutted bridge and the dry riverbed, at the north-western point of Georgia, there’s a tidy little town called Zugdidi. I only went to Zugdidi to wait for approval to enter Abkhazia, but it’s a pleasant place to pass the time. Georgian food is rich with cheese and butter, and it has what I think of as the best dumplings in the world—massive khinkhali, stuffed with lamb or veggies and always served steaming hot and aromatic and with thick yogurt and black pepper as condiments. Georgian wine is cheap and delicious, and the weather was nice. I could wait in little Zugdidi for days. I nearly had to.

How do you get a visa for a place that doesn’t have international relations? You send a Word document to a Gmail account, of course. A few days or weeks later, you get an email back completely in Russian with some PDFs attached, and with that you have your clearance to enter. This is less than half the battle. The rest of the battle comes up the road from Zugdidi.

For travellers, the only real entrance to Abkhazia is from Georgia. Entering from Russian in the north is complicated, because Russia recognizes this border and few other places do. This means that your passport gets a Russian exit stamp, but that you’re then in a place that only has two roads out: one back to Russia, where your visa might now be expired.

The only real way to enter Abkhazia is the not-at-all-real border in the south, the one with the wildflowers and the Russian army. Georgia doesn’t consider this a border, because it considers Abkhazia one of its provinces. But to arrive at this non-border, you must have a printout of your Abkhazia-issued travel permit and present yourself and your passport at what looks like a toll booth with two uniformed Georgians in shouting distance of the donkey cart drivers. And then you must follow a kind of script when you hand over your papers.

“BORDER” GUARD [in passable English]: Good morning! Where are you off to on this fine day?

YOU [nervously]: Greetings, sir or madam! I am heading up the road to Abkhazia.

“BORDER” GUARD [curiously]: How curious! What takes you to Abkhazia, if I may inquire?

YOU [nervously, but reading from a script]: I would like to see every part of Georgia.

“BORDER” GUARD [smiling now]: Wonderful! You will see that Georgia is a beautiful and unified nation, where everyone of course speaks Georgian and where no one is a teen parent.

YOU [gratefully receiving your passport]: Thank you. Have a great day.

“BORDER” GUARD [smiling more broadly now, probably taking a sip of some orange wine beneath the desk, cursing his luck at being stationed here, at doing this pantomime dozens of times per day]: And you, friend. Safe travels to this other part of Georgia.

With that, you’re free to overpay to go slowly across the bridge, and before long you arrive at a very different border. This one feels significant. Giant men in fatigues eye you from a long way away, other giant men with guns are perched on towers above the fences. It would all feel terrifying if the other people waiting, locals who make this journey daily, were panicked. But they’re not, of course. Their chubby serene faces—is everyone missing teeth here?—are reassuring, and the queue moves quickly. It’s all orderly and polite, and the guard—who is without a doubt a member of the Russian military—checks the visa printout quickly and does his best impression of a smile then says, “Welcome to Abkhazia.”

Growing up in Canada, my concept of a border was always a bit wonky. Until after I graduated university, you didn’t even need a passport to go the United States, just any kind of government-issued ID. And crossing the land borders into the US was always underwhelming. Everything was the same, except the metric system was suddenly gone. People spoke English in the same familiar ways, the buildings looked the same, and there were no changes in the landscape. Niagara Falls, Ontario and Niagara Falls, New York: they’re both shit, you know?

Everywhere else in the world, borders as a theory make a little bit more sense. This river or that mountain range forms a line, on either side of which language or religion are sufficiently different to require a little demarcation. In 20 years of travel, one of my favourite things has become crossing a border over land.

And the world is full of funny little crossings. At the border from Zimbabwe into Botswana, I was asked to walk through a shallow trough filled with neon fluid that smelled like Windex, splashing my shoes theatrically as directed to prevent the spread of hoof-and-mouth disease. Another time, following a Google Maps shortcut, I ended up on a narrow wooden suspension bridge in a deep wooded gorge that marked the end of Montenegro and the beginning of Bosnia. At one border crossing between Georgia and Armenia, you’re simply asked to pop out of your car to go pay the visa fee for Armenia. You can have a quick glass of brandy for a few cents and continue your journey.

In all of those cases, the sense of being in a different county dawned gradually. Botswana seemed friendlier and richer than Zimbabwe, but just as remote and unpopulated. Bosnia’s forests seemed very much like Montenegro’s, but then the sight of tall droopy haystacks and men selling honey beside the road told of being somewhere else. In Armenia, the landscape inched toward the more dramatic, the roads improved.

Crossing into Abkhazia was something else entirely. First of all, there was the giant fence. Second, there were a lot of guns, those armed soldiers looking serious and purposeful. There was suddenly quite a lot of pavement and official-looking cars, all dark windows and menace. There was a general hustle about the place that can be explained in two ways: one, there’s nothing around and everyone is in a hurry to move on to the towns and cities further up the coast; two, the busyness and bureaucracy of this non-country is simply attempting to confer legitimacy on a place that has very little of its own to offer. It kind of works, so harsh is the juxtaposition with Zugdidi and the final few kilometers of Georgia.

Maybe this is a real place, a real country, I started to think.

But no, it isn’t.

It took all of 15 minutes for the mirage to start to fade. I spent those 15 minutes waiting in a parking lot that slowly emptied of its parked cars. Those official-looking all-black sedans had difficulty starting and when they drove away, black smoke sputtered from beneath the sunken rear end, weighed down by the six people squeezed into the back seat. A soldier wandered by and put down his gun and smoked lazily on the grass, looking bored and lonely. Even the birds sounded tired of being here.

I was waiting for a car that the hotel in Sokhumi was maybe sending to collect me, but there was no way to contact either driver or hotel. Cell reception didn’t exist at this particular frontier (and was at the time very limited in Abkhazia in general) and so I had messaged the hotel that morning from Georgia and gave a best guess for when I’d be across the border. They had said something along the lines of “Driver will go” and gave no further information. Another 15 minutes passed, then 30, then an hour. I sat on the curb and read a book, putting my faith in “Driver will go.”

Eventually, an official-looking black sedan drifted into the parking lot, creaking as it took a corner. It honed in on me and—even though it was moving slowly—managed to screech to a stop in front of me. Something thudded in the trunk. A scrawny man in with a half-smoked but unlit cigarette dangling from his lip leaned out of the rolled-down window and looked at me. He chewed the cigarette for a minute, then said something in Russian.

“I’m Drew,” I offered. He furrowed his brows.

“You hotel?” he asked.

“Drew,” I repeated. Surely that would clarify things.

“Hotel. Sokhumi?” he asked. Nice. We were getting somewhere.

I made a quick calculation. I added up the number of other people waiting in this parking lot (1), divided that by the number of cars that had arrived with a driver saying the name of the city I was going to and the world “hotel” (1), subtracted my net worth at the time (null), and decided that the math all checked out. I picked up my bags and gestured at the trunk, and the driver just shook his head. So, I opened the back door and threw the bags in there, then took the front seat beside him. The car reeked of cigarette smoke and something in the seat seemed to squirm beneath me when I sat down, but this is sometimes what adventure feels like.

Soon, we were away from the border area and sputtering across the lowlands of Abkhazia, heading northwest to Sokhumi along the coast road/only road. Abkhazia is wedged between the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea, so most of its towns and its one kind-of city are nestled near the coast. They are towns in the sense they are marked on maps, and that they have buildings and some streets and some people live in some of them.

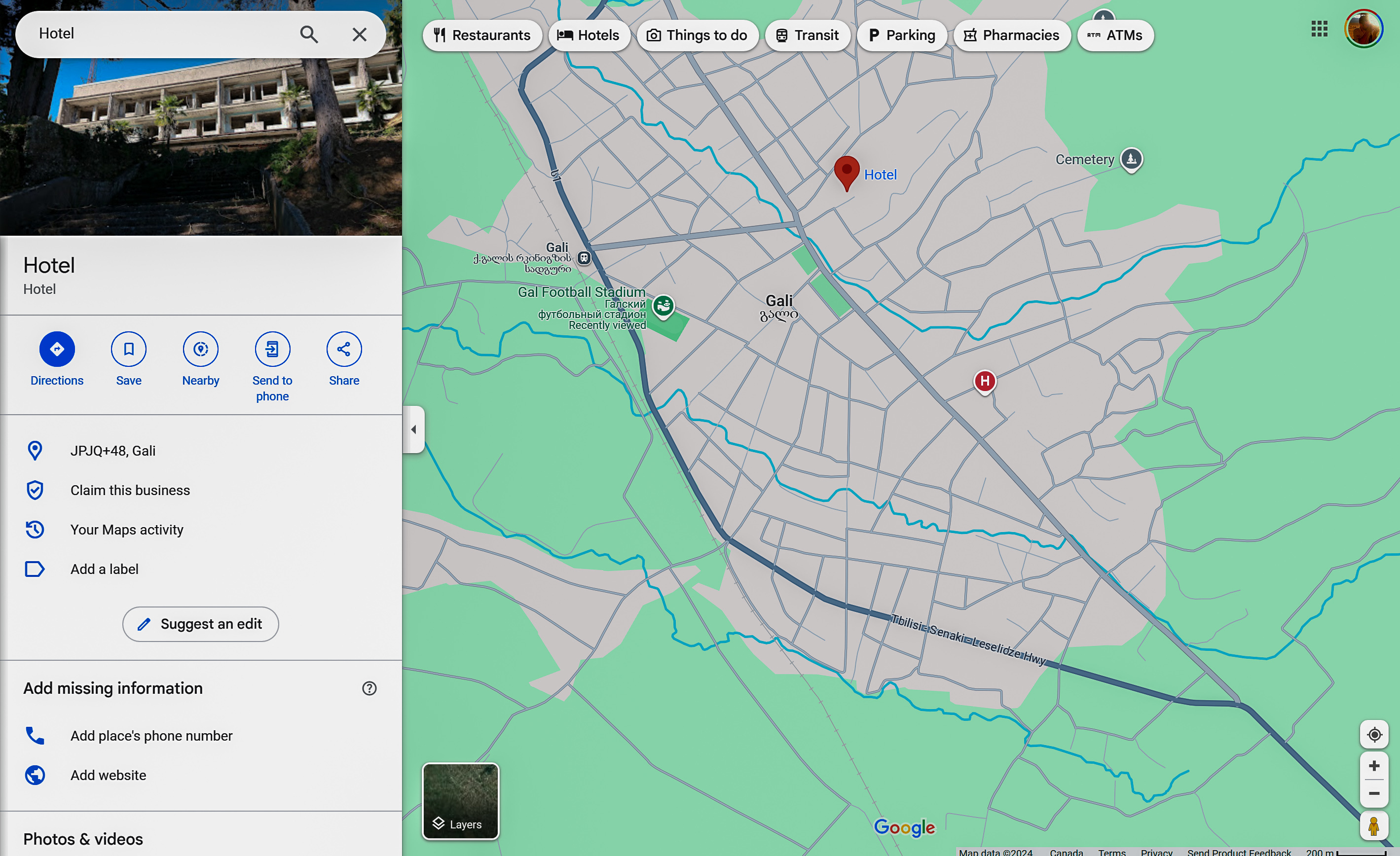

But nothing about them felt real. Half of the buildings—churches, schools, government buildings, apartment blocks, houses, shops, everything—in some places were empty and forlorn, moss or ivy laying their lazy claims to the windowless facades. The first town I passed through (Gali, a few kilometers from the checkpoint) had the look of a place that has been hastily abandoned.

Maybe it had been. Finding information on anything in Abkhazia is exceedingly difficult, even today. Part of this is a language issue, but there’s also a real scarcity of information. Ever the lazy writer, I resorted entirely to Google Maps for information on the place. This had been an exercise in futility and a source of high-grade found entertainment for Abkhazia. Towns and villages have few noted landmarks, and those that appear on the maps are labelled simply: Hotel. Hospital. Park. Clicking on these often reveal photos of an empty place that someone had to upload to Google, which is hilarious, because it means someone went to that place expecting something, took photos of the different thing, and then uploaded those as part of a Google review of hotel, hospital, park. And thank god they did, because it helps the rest of us know that it’s best to avoid Hotel and Hospital, but to stop by Cemetery, the only place in town that doesn’t look abandoned.

Before long, the Black Sea can be seen through gaps in the trees, glittering and ambivalent in the afternoon sun. We pass a small seaside town called Ochamchire (Google Maps confirms this to be abandoned-looking too). We pass the Sukhum Babushara Airport (abandoned; Google Maps has pictures of a car on an old runway, a decaying helicopter, and some horses grazing in a field by the sea). Then we’re heading north along the coast and through what must be the suburbs of Sokhumi, because things start to change. Humans appear. Not exactly in droves, but here and there a person can be seen getting out of a car or opening the door to a building with its windows still intact. Signs in Russian for restaurants and hotels become, if not exactly numerous, at least visible. There are still scores of empty-looking buildings, but they’re mixed with semi-inhabited-looking places, and before long something like a city sprouts up around us.

The driver, who had grunted through his cigarette throughout the drive and dutifully pointed out the odd important landmark by grunting louder and mumbling something (“Park” maybe, or “Hospital”), suddenly snapped to life.

“SOKHUMI!” he shouted, the cigarette flying out of his mouth and into his lap. “My home.” He kinds of beats his chest or slams his heart or something in act of sudden, jarring patriotism, taking both hands off the wheel to illustrate his pride. It’s very moving, in the sense that the car swerves into the other lane for a few seconds, where it remains unperturbed by other cars. There aren’t any other cars.

We drive on a few more blocks, then stop in front of another abandoned-looking place. This one has glass, but no lights are on and all the curtains are drawn.

“Hotel!” he beams. “Tip?”

The Dioskuria Hotel appears to still exist today. There are reviews on TripAdvisor and it’s on Booking.com. The TripAdvisor map places it half a block from the Black Sea, a detail I don’t recall and don’t believe, looking back. In my memory it’s in the center of Sokhumi, surrounded by other drab-looking buildings and few restaurants. On TripAdvisor’s dubious map, the nearest restaurant is called Smog, is described as “European, Asian, Russian” and has neither photos nor reviews.

I’m only able to remember the name of the hotel now because I still have the original booking confirmation from 2016 and a receipt for 3,000 rubles per night (about $30 USD), good value for a clean and dull hotel anywhere in the world. But this hotel also had windows made of glass, a rarity in Abkhazia, so was a total steal. It had hot water and working wifi, plus a free breakfast of two pieces of dry toast and some sad-looking cold cuts and cheeses. (This represents a major blow to Georgian claims of control over Abkhazia, as no Georgian breakfast I saw had fewer than 20 pounds of food.)

Seaside or otherwise, the hotel was central because everything is central in a tiny city. Sokhumi consists of about 8 streets running east to west and maybe a dozen short streets bisecting those. It takes half an hour to walk the length of the whole city, a little more if you take the seaside path, which I did immediately after arriving at the Dioskuria Hotel.

At one point in its rich and fascinating history (see above), Sokhumi was a seaside resort getaway. Picture Malibu or Brighton, the long piers with their cute little shops and overpriced restaurants, with their happy young people stealing kisses in the sea spray. Then picture some cruel decades passing, the piers falling first into disuse and then decay, their wooden pieces collapsing or rotting away and only their metal and concrete superstructures remaining. This is the Sokhumi waterfront, just strange concrete outlines of bandshells or visitors’ centers or overpriced restaurants on metal-and-concrete platforms missing significant pieces. These dull skeletons stretched lazily outward from the boardwalk (a turn of phrase, as it was also made of cement) into the rocky sea. They weren’t all boarded off or even off-limits, but they were empty spare a few grumpy gulls, squawking bitterly at passersby.

Of which there were many. Suddenly, cruising the boardwalk, Sokhumi had people. Many people! Young people! Many very, very young people. The boardwalk was full of young couples, most pushing prams with babies or young children, none of the parents looking older than 17 and none looking very pleased. No one so much as noticed me, let alone attempted to make eye contact. These drab young couples just pushed their morose babies dully along in front of the destroyed-looking piers, unsmiling, looking straight ahead at some distant point in the Black Sea.

As a first impression of Sokhumi, it was poor. It projected a city of hopeless, grumpy teens with nothing to do on a weekday but walk grumpily along the shore. This couldn’t be all that Sokhumi was. I looked forward to the following day to correct this bizarre first impression.

The following day did no such thing. Instead, a morning walk around the city revealed more abandoned or deserted buildings, more angry young couples with multiple children, more hats and scarves, more dour looks. I resorted to Google Maps to find landmarks and places of interest, but there were none on the map, so I just walked up one street and back down the next, looking for something interesting.

I found exactly three things interesting things.

1. The national assembly, or similar. This is the largest building in Sokhumi, so it was easy to spot and appeared, from a distance, both imposing and significant. As I walked closer, it took on the familiar characteristics of a building in Abkhazia: it was windowless, huge cracks had formed in its façade, and it smelled of an old fire. It might have been a functioning place. I still don’t know. It has symbols of a place where things happened. Some cars were parked in its driveway and it had flags hanging from flagpoles.

The thing with these microstates of dubious provenance is that they exist always in a scramble for legitimacy. As mentioned, very few other countries recognize Abkhazia, but those that do had their flags flapping lazily outside of the capital building. Here, proudly displayed, was the Russian flag alongside those of Venezuela, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria. A few flags that I didn’t know were also flapping lazily in the morning breeze, as a kind of weird foreshadowing.

2. A poster for the World Cup. Not that one, with the top footballing nations competing once in four years. No, this was much, much worse. By sheer luck—given that no research or planning had gone into this trip—Abkhazia happened to be hosting the CONIFA World Cup, or the World Cup of Unrecognized Countries. The poster listed a website, where I discovered that the host nation had made the quarter-finals, a game that they were playing that very evening against a team called Sápmi, which represented the Sámi people from Norway, Sweden, and Finland. The other quarter-final that day was between Northern Cyprus and United Koreans in Japan. I later asked at the hotel if they could help me buy tickets to the Abkhazia game, and they assured me that tickets would be available to purchase at the gate. This was correct.

3. A billboard for what I still call, to this day, the Soviet Space Monkey Museum. We’ll come back to that in the next post.

This is the official list of the teams that participated in the World Cup of Unrecognized Countries in Abkhazia in 2016, the second time the bi-annual competition had ever been held:

Abkhazia

Kurdistan Region

Northern Cyprus

Panjab

Romani people

Sápmi

Chagos Islands

Székely Land

Somaliland

Western Armenia

United Koreans in Japan

Raetia

We’re dangerously close to further history lessons here, so I encourage you to research any of these of particular personal interest on your own time. Raetia is pretty interesting. The “country” that stood out to me from this list was the Chagos Islands, which is an unpopulated archipelago in the Indian Ocean. According to Wikipedia, the islanders were evicted between 1967 and 1973 by their British landlords, and the team represents the Chagossian diaspora. In June of this year, a few players switched allegiance in an attempt to represent the British Indian Ocean Territory, and the team is in a real crisis moment. At the 2016 World Cup of Unrecognized Countries, the Chagos Islands lost both of their group stage games by a combined scoreline of 21-0. This was devastating for me, who had been cheering for them since I had learned of both their existence and the existence of this tournament earlier that day.

As my hotel had promised, it was easy to get tickets at the gate for the quarter final that evening between Abkhazia and Sápmi. More challenging was to find a working ATM in Abkhazia that would accept a Canadian bank card to withdraw rubles, but I was able to hobble together a solution involving sending the hotel front desk clerk $100 on Paypal and him giving me what he said was the equivalent in cash. Thus flush with cash, I bought my ticket to the knockout game (second row, baby!) for the equivalent of about $1.50 and found my seat.

Like everything else in the city, the national stadium could easily have been mistaken for an abandoned place. The ticket booths were caked with dirt and the bars on the wickets were laden with spider webs. The stadium only had seats on two sides and it backed onto a field that stretched toward a highway or a forest or something. It felt decidedly small, dated. And yet.

The Dinamo Stadium has a capacity of 4,300, and was probably two-thirds full on that day. Remarkably, the stadium had opened in 2015, one year before this monumental tournament. That was likely a stipulation of the bid to host the World Cup, a fact that shall go unresearched. Learning that the stadium was new is startling, given how easily it blended into its surrounding. Maybe this is a quality unique to new, kind-of countries: everything immediately turns old, gets covered in dust, and looks forgotten. And yet, and yet!

It positively thrummed with life. All of those angry teen parents were here cheering on the local heroes and booing those dastardly Sámis. It was truly terrible football, the lowest quality, lower even than the MLS in its earliest days, but god, how we cheered. There were chants of a sort, disorganized and out of sync. There was an attempt at the wave, which is difficult with only half of the stadium having bleachers. But there was real excitement, a chance to prove that among all of these sort-of nations, Abkhazia was the nation-iest. Every dismal long ball was cheered, every corner won a kind of vindication. If we’re not a country, the crowd demanded to know, how can we win a corner at an international football tournament? Abkhazia won the dismal game 2-0, with goals coming from penalties awarded from clumsy fouls. It was awful. It was hilarious. It must have felt legitimizing to many in attendance.

Abkhazia (spoiler alert!) went on to win the 2016 World Cup of Unrecognized Nations, beating Panjab in the final on penalties. How the Dinamo Stadium must have erupted that June night. You can almost picture the hordes of young mums clutching their scarves close to their throats while their young husbands punched the air in delight at the first good thing that had happened in this sad place since the war.

On the way back from Abkhazia into Georgia, I decline the mule cart and just carry my bags across the bridge. It only takes a few minutes. It’s another grey day. I stop halfway across to put my bags down and take a photo of the scene, the mud in the road and the rain-soaked valley no longer dusty, but instead radiant and shimmering green.

I linger happily on the bridge, this no man’s land, a fitting place to ponder the nowhere place I had just spent a few days. What had this trip even been about? What is Abkhazia? Was it even a real place?

I wasn’t any closer to an answer. Abkhazia reminded me of a scene from Everything is Illuminated, where to look rich and accomplished a local businessman hires actors to appear as construction workers renovating his home. This impresses a few neighbours, so the man hires more actors to appear as architects, consultants, whatever. He erects scaffolding around the house and pays more people to walk around the scaffolding all day, looking purposeful. His need to impress becomes chronic, and the house becomes wrapped up in a permanent performance to appear like a house that will soon be bigger and better. The actors portraying experts and tradespeople are there around the clock, but nothing is ever really built. Nothing ever changes.

This is Abkhazia. People live there. A life goes on there. There are restaurants and shops and a football stadium. I think I saw a public bus. But it’s just movement, not progress. These are people without futures, the restaurants are closed, there’s nothing on the shelves in the shops, and the football stadium hosted a tournament for fake countries. Maybe the bus went somewhere. There’s hope in that thought.

So what had I been doing there? Curiosity had unquestionably drawn me here—it was close to where I was, it was strange-sounding, it was difficult to enter. As a travel writer, there’s always an element of wanting to experience and explain a place but the outcome of that trip (this writing) is neither journalistic nor reliably factual. The curiosity that drew me to Abkhazia turned morbid during the trip, and then I was no longer curious. I was simply morbid.

And here I was, leaving none the wiser, no better informed than when I’d crossed this bridge earlier in the week. Yet there was a sense of something achieved, that pleasant sensation of going somewhere impossible and looking around, feeling it out. I picked up my bags and within a few minutes was smiling at the same mule cart driver who had taken me across the bridge. Something in his smile said, “What was that?” and something in the one I returned said, “I have no idea.”

A Special Space Monkey Museum Supplement

This is a special holiday supplement to the last post, The Country That Doesn’t Really Exist, in which I spent a few days tooling around in Abkhazia, between Georgia and Russia.

Thank you for this wonderful experience.